|

| Some of the Participants at the Inaugural Meeting of the Breadalbane History Group |

About twenty people from the Breadalbane community met at the Breadalbane Hall on Sunday 27th November to share photographs and stories of the history of the region. I was invited to give a talk on the importance of local history. My talk was rather personal, but I thought this was important because the group hope to interview some of the residents of the area, and, having an interest in local and family history, I thought it important to outline some of the issues that one usually encounters when delving into the past. I have added the transcript from my talk here. It is rather personal at times, but so be it!

The Importance of Local History in Australia

Dr Michael de Percy

Good afternoon. I am pleased to have this opportunity to address you here today and I thank you for the invitation. I would like to acknowledge that, according to the traditional owner’s map from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, this meeting is being held on the traditional lands of the Gundungurra people, which intersects with the traditional lands of the Ngunnawal and Wiradjuri peoples, and I would like to pay my respect to elders both past and present. I will explain a little later why doing so is important to me, and I will do my best to put this in the context of this meeting here today. But let me start with my interest in history.

|

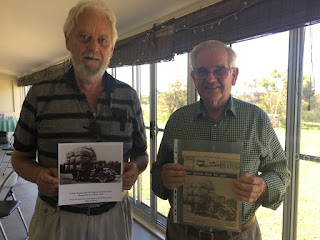

| Paul Ings and Terry Hannan with their old photographs |

In my political science research, I am particularly interested in how decisions made in the past help or hinder the choices we can make in the present. This is obvious in networked infrastructure such as roads. Le Corbusier, writing about architecture in the 1920s, made a point about how the roads in Paris were based on tracks carved by beasts of burden over many centuries. While there have been changes over time, a good deal of the road network still traverses those same tracks and may continue to do so for some time. The past, once traditions, habits, and patterns become entrenched, can be difficult to change.

In Australia, we have a similar situation with internet access, although it is often difficult to convince others how decisions made at the time of the telegraph continue to impact upon broadband access today. Many technologists will tell you that the telegraph has nothing to do with broadband, but the interpretation of the wording of section 51(v) of the Australian Constitution, which gives the Commonwealth powers for “telegraphic, telephonic and other like services”, and the way these powers are put into practice, explains why your local councillor cannot help you with your internet connection or speed up the delivery of the NBN. In countries such as Canada, different approaches to deploying the telegraph have resulted in a much stronger role for municipal governments in enabling broadband.

This is all history, and while it may not mean much today in the context of the NBN, pretending that the decisions made in the past have not influenced the way we do business in the present is little more than denying the impact of history. And so it is with local history, and I would like to talk to you today about how local history can play an important role in not only understanding where we came from, but where we could go in the future if only today’s choices were better informed. Drawing on Karl Marx, Bogdanov suggested that “the dead lay hold of the living”, and in many ways, our present is lived in the very future established by generations past. Understanding history, then, is to me something quite necessary. And in Australia, where the history of European settlement has been rather short, we still have a lot of work to do.

I would like to start by talking about family history, and then move to the importance of local history, particularly in this region. Why family history? Well, to me, local and family history are often linked. I am sure for any of you who have already delved into the history of this region, you will be familiar with the names of the families that bring that local history to life. Indeed, I suspect that many of you here today will be members of those same families. But like all families, there are many myths that become legend that eventually become accepted family facts. It is not unusual for people to use these accepted facts as key pillars of their identity. In my own family history research, I remember the first fact was that my paternal great-grandfather had been a member of the light horse, had served at Gallipoli, and had won some sort of medal for bravery during the Great War. The truth was that he joined the 33rd Infantry Battalion and went to France in 1916, and was subsequently gassed twice. He was charged with being absent without leave a few times, but he never did receive a bravery medal. But the truth didn’t mean he wasn’t a hero. He volunteered again in the Second World War – I believe he lied about his age. His second time in the infantry didn’t last long – he appears to have become a sapper and worked building roads. Very different from the family legend, to be sure, but fascinating nonetheless. There are many more family legends that I have “myth-busted”, and I will share one more of these with you.

I was fortunate enough to have met each of my great-grandmothers. My maternal great-grandmother told us how she was Cherokee Indian. The family believed this for more than two decades. We were also told that there were no convicts in our family – none at all. But just recently I discovered that my great grandmother was born on Walhallow Mission. Not only was her great grandmother an Aboriginal woman, but her great grandfather was a convict. Her own father appears to have been an Aboriginal man, too. If I were to believe the historical trail she left behind in her marriage certificates and her own mother’s death certificate, she had two different European fathers. There was also a view that my maternal grandmother’s family were Irish ne’er do wells, but I have been able to trace her father’s family back to the 1500s in Kent, England. So I have busted many myths, but the truth has always been more fascinating than the family legends. But I do not recommend this approach if you have created your own identity based on family legends! But the truth is there are many stories like these waiting to be discovered.

Now to local history. But allow me to digress. It wasn’t until 2006 that I first travelled overseas. Since that time, I have visited the old Quebec City and the Maritimes in Canada, the ancient ruins at Palmyra, Syria (well before the current war), the Great Pyramids of Egypt, the site of the Great Library of Alexandria, the fascinating ancient city of Petra carved out of the mountains in the deserts of Jordan, made famous by the scene in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the Baptism Site on the Jordan River, the great old city of Jerusalem, the ancient burial crypts of Bahrain, the Buddhists monuments in Thailand, ancient pagodas in China, the ruins of St Pauls in Macau, the tenements of Glasgow, and many of the famous historical sites of London and Paris. And then recently, I moved to Gunning, NSW, population 500.

I first visited Gunning last year. I had seen the signs, but had never driven beyond Gundaroo. While conducting research for a radio show I presented on the words of Henry Lawson set to music, I stumbled upon Max Cullen’s autobiography. At the end of the book, Max states proudly that he lives in the old Coronation Theatre in Gunning. I asked my wife if we had ever been to Gunning – we hadn’t – and that afternoon I made an offer on the house we now live in. It is a federation house built by the Caldwell brothers for Samuel Bush in 1926. My great-grandmother owned a federation house in Haberfield, and I have always wanted to live in one and now I do.

Between the time of the offer until the settlement date 3 months later, I discovered that the original owner of the block of land was a journalist who bought it in the first town lot release in 1875. By the 1890s, he was bankrupt and the land changed hands several times until purchased by the Bushes. In 1949, Samuel Bush gave the house to his son as a wedding present. I believe they lived in that house until the 1990s, and I am pleased to say that after numerous transactions, it is now in good hands. But I couldn’t stop there. I have been fascinated with the village of Gunning. Every building has its own story to tell. My favourite piece is a story by a journalist written in 1878. He walked from Meadow Creek up to the Public School on Yass Street, crossed the road and walked back down the other side, describing every building along the way. Many of those same buildings are still there now. It is not unusual to become addicted to such a quest for historical knowledge, and it is one of the few healthy addictions!

In June this year, I ran two workshops on using Trove, the National Archives, and the Australian War Memorial records for family and local history research. Both workshops were fully booked out and the team at Trove and ABC 666 in Canberra were interested in what we were doing at a local level. Participants were encouraged to bring along their own research projects, and after a brief introductory session on the database, I shared some of my tips and tricks.

Each participant found something interesting and relevant to their research projects. One was able to confirm a family legend about a relative who had performed at the Sydney Opera House, others were able to learn about the history of their house or about family members who had served in the military.

Some of the tips and tricks I shared included to notice the typing conventions of particular periods and to recognise repeated patterns in the transcription errors. For example, when looking for street names, it was once common for newspapers to hyphenate the street name. Yass Street then becomes Yass-street. If you use quotations marks and search for "Yass-street", then it excludes the many articles that relate to Yass the town, rather than Gunning’s main street. Even simple tips like using a minus sign to exclude certain words can improve the search results. More tips can be found in Trove's Help system.

After a while, I was able to recognise standard errors in the transcription. For example, Saxby-street often appeared as Samby-street. By searching for the error, I found most of the missing links in my project. And each time I found an error, I corrected the text so that future researchers will have an easier time searching.

One of Trove’s important functions is the ability to fix transcription errors. If there is a particular topic or region of interest, a committed group of researchers can improve access to the historical records by enabling better search results. It can also be useful to have shared lists on particular topics.

As a result of the workshop, local history research has improved as the accuracy of the transcriptions of local articles has increased and searching Trove has become much easier.

The most recent workshop held at Gunning Library focused on Australian military service records using Trove in conjunction with the online collections from the National Archives of Australia and the Australian War Memorial. We are hoping to make further exciting discoveries about the town that will eventually feed in to planned walking tours of the village.

Trove provides rural and regional communities with access to all sorts of digitised information held in collecting institutions around the country, including maps, photographs and music. Trove’s advantage is that it provides information that you would otherwise have to travel to to find. Indeed, Trove overcomes the barriers of distance and many local libraries provide internet access so you can search Trove and its many treasures. But as I said - be careful – it can be highly addictive!

And what I have realised is that while we do not have the Great Pyramids, or ancient Greek and Roman ruins, in this fair land we have everyday stories that together form a rich tapestry of a nation forged out of the antipodes, and many of those stories are just waiting to be told. I recently read Robert Macklin’s book about Hamilton Hume, and, while somewhat starry-eyed in its patriotism, I couldn’t help but feel that Hume’s story is part of my own. Hume was a native born “currency lad” while his historical companion, William Hovell (as we were taught at school - but I am reliably informed that the name should be pronounced “Hove-ell”) – was a “sterling” or English-born. Hove-ell attempted to claim most of the glory for Hume’s bushmanship and navigation skills but was later found out. Charles Sturt, although another “sterling”, had a good deal of respect for Hume’s abilities and did all he could to ensure that Hume received the recognition he deserved. Nevertheless, the “Hume River” is now known as the “Murray River” because Sturt, fascinated by the prospect of finding an inland sea, thought he had discovered another river. Macklin suggests that Sturt may well have regretted this transgression.

But as we know, Hume’s name has been recognised in the name of the highway nearby that traverses much of the original track established by the famous explorer. And while I have no wish to put down Hove-ell, Hume’s importance to this region and the legends of his abilities to negotiate with and befriend the Indigenous peoples, his expert bushcraft, navigation skills and so on, all contributed to the folklore of the Australian bushman, a theme later captured by the official historian of the Great War and founder of the Australian War Memorial, Charles Bean, in developing the now celebrated legend of ANZAC.

So legends, myths, myth-busting, stories of the past and their influence on the present – all of these things are part of our local history, often intersecting with the history of our own families and, en masse, forming the rich tapestry of our national culture and identity. Which brings me to the purpose of this meeting today.

Often, when I discuss local and family history stories with older members of the family and community, it is apparent that much of the knowledge of the 19th and early 20th centuries, if not already lost, is no longer part of our living memories. You may never know if you are of Aboriginal heritage if, like me, your ancestors had no birth certificate and stories were devised to hide that fact. Legends may also hide your convict heritage or, indeed, your ancestors may never have been at Gallipoli. Such things are part of living. But what of our local communities? Is Breadalbane and the pioneers who forged a community here, the coach services, the railway station, the Aboriginal peoples who once walked this land, Thomas Byrnes who may or may not have been a bushranger, the battle between troopers and Ben Hall’s gang nearby, all to be relegated to the dustbin of history because we did nothing about it?

Paul Kelly once wrote that Australia suffers a “settlement” mentality where we rely on the government to provide our every need, and it is unfortunate that the funding of our national cultural institutions is steadily being eroded. But our local communities are now more important than ever, particularly in the regions. And in re-building, re-creating, or re-imagining these communities, whether socially, economically, or spiritually, I believe it is important to begin at the beginning. To begin with history.

But that history begins with you. On the website “Aussie Towns”, under the heading “Useful websites about Breadalbane”, it reads: “There are no websites with information about Breadalbane”. Yet the National Library’s Trove database provides information about a number of interesting things about the region, including:

- Iron, gold, and copper mines were worked nearby;

- There were numerous engagements between troopers and the bushrangers Gilbert, Hall, and Dunn here

- This land is known traditionally as “Mutmutbilly”

- The centenary holidays in 1888 were “very quiet” here

- A photograph of the honour roll from the Second World War

- A photograph of the highway in 1938

- A photograph of the centenary plaque at the school from 1968

I am certain there are many more stories hidden in Trove, but even more so in your personal collections. And photographs from the past are rare, especially those that are digitised and freely available to others.

There are of course some issues with family history. One of my great-grandmothers refused to tell us who her father was. One of our well-regarded ancestors was a Salvation Army officer who mysteriously “disappeared” after the Great War. His medical record reveals that he spent a very long time recovering from a particular disease in Paris, and then married a nurse in England and moved to Canada, never to return to his native land. There are appropriate reasons that historical records are not often available to the public until well after our ancestors are but distant memories. But this does not help us to understand where we came from, how our values, assumptions, beliefs and expectations were forged by generational experience, or what our ancestors looked like.

Fortunately, technology is providing us with greater access to our knowledge of the past than ever before. But it is a truism that technology can only produce what we put in to it – the basics still apply. Therefore, I encourage you to support this local initiative to capture the history of this village. There are many benefits to doing so, be they social, economic, or spiritual.

But more than that, while the cultural cringe that has plagued Australia since European settlement is far from dead, there is a rich history in this region just waiting to be discovered. And although I have been fortunate enough to see the Great Pyramid, the last surviving Ancient Wonder of the World, to see a version of the Temple of Artemis at Jerash in Jordan, to walk on the Mount of Olives, to touch the walls of the old fort at Quebec and to stand on the walls of Saladin’s Qalat Ajloun (or Ajloun Castle), to enter centuries-old Chinese pagodas and to see some of the ancient wonders at Palmyra in Syria that are now no doubt lost to us forever, there is a rich history right here in our own back yard waiting to be discovered. From the history of the Indigenous peoples dating back some 800 centuries before “ancient” times to the end of the railway station here in 1974, there is much to record, and much to be lost if we do not act soon.

I wish you well in establishing this group, in recording your individual and collective histories, and I commend to you the Gunning and District Historical Society as a vehicle to help you on this journey. Thank you and good luck.

Comments

Post a Comment